Welcome to part 2 of the ODX Andropause & Low T Syndrome Series. In this post, the ODX Research team reviews the biology and physiology of what lies beneath the hormonal change known as andropause and Low T Syndrome.

The ODX Male Andropause Series

- Andropause Part 1 – An Introduction

- Andropause Part 2 – Biology & Physiology

- Andropause Part 3 – How to identify it

- Andropause Part 4 – Lab Assessment and Biomarker Guideposts

- Andropause Part 5 – Clinical Determination

- Andropause Part 6 – Lab Reference Ranges

- Andropause Part 7 – How do we treat and counteract andropause?

- Andropause Part 8 – Lifestyle approaches to addressing Andropause

- Andropause Part 9 – Optimal Takeaways

- Optimal The Podcast – Episode 9: Andropause

Serum T levels are at their maximum between age 25 and 30.[1] An observed decline after age 40 had traditionally been attributed to “normal aging.” However, more contemporary research suggests that annual age-related decline is no more than 0.5% or less in healthy men, so LOH is not simply a phenomenon of aging.[2]

Physiologically, LOH and related declines in serum T may be associated with a decrease in hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone, disruptions in androgenic negative feedback systems, or possibly a decrease in sensitivity and responsiveness of testicular tissue.[3]

Researchers hypothesize that reduced sensitivity of testosterone receptors may account for some of the symptoms of LOH. Decreased receptor sensitivity in the central nervous system could help explain the decline in sexual desire seen in LOH as well as the need for higher doses of T to achieve symptom relief in some individuals. Reduced sensitivity could also help explain why some individuals have LOH symptoms despite “normal” T levels.[4]

A decrease in serum albumin and an increase in SHBG will also decrease the amount of biologically active T available. Since SHBG levels tend to increase ~2.7% per year with age, a decrease in active T is anticipated.[5]

Increased conversion of testosterone to estradiol via increased aromatase activity is also observed with advancing age and may contribute to low T.[6]

Chronic metabolic disorders, including chronic inflammation, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity may reduce serum T by a factor of 1.5-3.6.[7]

Diabetes appears to be a particularly significant factor in LOH and may accelerate its development.[8] However, a vicious cycle may underlie the association as declining T levels lead to reduced insulin sensitivity and increased risk of glucose dysregulation and diabetes. The metabolic effects of testosterone include maintaining muscle mass and reducing visceral fat. Therefore, its decline can contribute to the development of metabolic syndrome.[9]

Acute conditions can reduce testosterone temporarily, these include stroke, myocardial infarction, gallbladder surgery, head trauma, severe burns, and even acute colitis.[10] It is important to repeat T testing to ensure that levels are chronically low before diagnosing LOH. Ideally, two additional measurements should be taken at least 2-4 weeks after the initial low T reading.[11]

Risk factors for low T and LOH include:[12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20]

- Acute illness

- Asthma

- Diabetes mellitus

- Emotional stress

- Hemochromatosis

- HIV

- Hodgkin disease

- Hyperlipidemia

- Hypopituitarism

- Inflammatory arthritis

- Kidney disease, especially end-state on hemodialysis

- Lifestyle habits e.g., sedentary lifestyle, smoking, excess alcohol

- Liver disease, especially cirrhosis, fatty liver, NAFLD

- Medications may inhibit HPT axis (e.g., anti-depressants, glucocorticoids, opioids)

Medications may inhibit T production (e.g., chemotherapy, GnRH analogs, mitotane, ketoconazole - Metabolic syndrome

- In obese men, metabolic syndrome may be considered a risk factor for low T. However, in non-obese middle-aged men with a BMI of less than 25, low testosterone itself may in turn be a risk factor for metabolic syndrome and therefore cardiovascular disease.[21]

- Nutritional deficiencies

- Obesity

- BMI of 30 or greater is associated with a 13-fold increase in risk of LOH, likely due to increased pro-inflammatory cytokines, leptin, increased oxidative/nitrosative stress, and disruptions in insulin signaling.[22]

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Noise pollution (animal studies)

- Pesticide exposure

- Radiation exposure (ionizing and non-ionizing), testicular irradiation

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Toxin exposure (e.g., chlorine, disinfectant by-products (DBPs)

- Variations in tissue sensitivity to testosterone

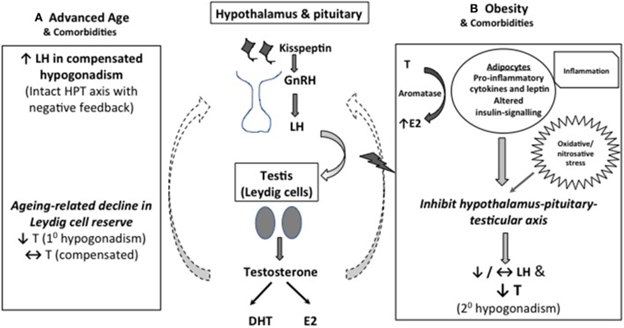

A mechanistic explanation for low serum T in middle-aged and older men.

(A) As Leydig cell reserve decline with aging, compensatory rise in luteinizing hormone (LH) occurs to maintain circulating testosterone (T) concentrations (compensated hypogonadism). In more advanced state, elevated LH can no longer overcome the diminished testicular function, leading to overtly low T levels (primary hypogonadism). (B) Obesity is the predominant cause of functional suppression of hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular (HPT) axis in middle-aged and older men, manifesting as failure of LH response to low T (secondary hypogonadism). Multimorbidity is also associated with both primary and secondary hypogonadism, albeit to a lesser degree. Excess adiposity has been linked to altered insulin signaling, oxidative stress and increased pro-inflammatory cytokines and leptin levels, which act in concert to suppress the central HPT axis. Adipose tissues also express aromatase which convert testosterone to estradiol, especially in the inflammed state, exerting inhibitory effects on the HPT axis.

Source: Swee, Du Soon, and Earn H Gan. “Late-Onset Hypogonadism as Primary Testicular Failure.” Frontiers in endocrinology vol. 10 372. 12 Jun. 2019, doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00372

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

Optimal Takeaways for andropause / Low T syndrome / LOH biology and physiology

Manifestations of LOH can be categorized as:[xxiii]

- Cardiometabolic (metabolic syndrome, changes in body composition)

- Physical (gynecomastia, loss of hair, loss of height)

- Psychological (mood changes, altered sense of well-being)

- Sexual (erectile dysfunction)

Fundamental causes of LOH include:[xxiv]

- Aging affects gonad function

- Luteinizing hormone increases to compensate for reduced testosterone levels

- SHBG increases with age

- Obesity

- Aromatization of T to estrogen occurs in visceral adipose tissue

- Testosterone receptor sensitivity decreases

Lifestyle and metabolic causes of LOH include:

- Aromatization of testosterone into estrogen

- Obesity

- Poor nutrition

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Smoking, excess alcohol

- Stress overload

NEXT UP: Andropause Part 3 – How Do We Identify It?

Research

[1] Liang, GuoQing, et al. "Serum sex hormone-binding globulin, and bioavailable testosterone are associated with symptomatic late-onset hypogonadism complicated with erectile dysfunction in aging males: a community-based study." American Journal of Translational Medicine 2018.

[2] Swee, Du Soon, and Earn H Gan. “Late-Onset Hypogonadism as Primary Testicular Failure.” Frontiers in endocrinology vol. 10 372. 12 Jun. 2019, doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00372

[3] Rao, Amanda et al. “Testofen, a specialized Trigonella foenum-graecum seed extract reduces age-related symptoms of androgen decrease, increases testosterone levels and improves sexual function in healthy aging males in a double-blind randomized clinical study.” The aging male: the official journal of the International Society for the Study of the Aging Male vol. 19,2 (2016): 134-42. doi:10.3109/13685538.2015.1135323

[4] Jakiel, Grzegorz et al. “Andropause - state of the art 2015 and review of selected aspects.” Przeglad menopauzalny = Menopause review vol. 14,1 (2015): 1-6. doi:10.5114/pm.2015.49998

[5] Decaroli, Maria Chiara, and Vincenzo Rochira. “Aging and sex hormones in males.” Virulence vol. 8,5 (2017): 545-570. doi:10.1080/21505594.2016.1259053

[6] Dudek, Piotr et al. “Late-onset hypogonadism.” Przeglad menopauzalny = Menopause review vol. 16,2 (2017): 66-69. doi:10.5114/pm.2017.68595

[7] Swee, Du Soon, and Earn H Gan. “Late-Onset Hypogonadism as Primary Testicular Failure.” Frontiers in endocrinology vol. 10 372. 12 Jun. 2019, doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00372

[8] Bakr, Attaa M., et al. "Diabetes Mellitus Accelerates Andropause in Aging Males." (2017).

[9] Ide, Hisamitsu, Mayuko Kanayama, and Shigeo Horie. "Diabetes and LOH Syndrome." Diabetes and Aging-related Complications. Springer, Singapore, 2018. 167-176.

[10] Dudek, Piotr et al. “Late-onset hypogonadism.” Przeglad menopauzalny = Menopause review vol. 16,2 (2017): 66-69. doi:10.5114/pm.2017.68595

[11] Decaroli, Maria Chiara, and Vincenzo Rochira. “Aging and sex hormones in males.” Virulence vol. 8,5 (2017): 545-570. doi:10.1080/21505594.2016.1259053

[12] Singh, Parminder. “Andropause: Current concepts.” Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism vol. 17,Suppl 3 (2013): S621-9. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.123552.

[13] Bhasin, Shalender et al. “Testosterone Therapy in Men With Hypogonadism: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism vol. 103,5 (2018): 1715-1744. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-00229

[14] Rao, Amanda et al. “Testofen, a specialized Trigonella foenum-graecum seed extract reduces age-related symptoms of androgen decrease, increases testosterone levels and improves sexual function in healthy aging males in a double-blind randomized clinical study.” The aging male: the official journal of the International Society for the Study of the Aging Male vol. 19,2 (2016): 134-42. doi:10.3109/13685538.2015.1135323

[15] Roychoudhury, Shubhadeep, and Rudrarup Bhattacharjee. "Environmental Issues Resulting in Andropause and Hypogonadism." Bioenvironmental Issues Affecting Men's Reproductive and Sexual Health. Academic Press, 2018. 261-273.

[16] Karakas, Sidika E, and Prasanth Surampudi. “New Biomarkers to Evaluate Hyperandrogenemic Women and Hypogonadal Men.” Advances in clinical chemistry vol. 86 (2018): 71-125. doi:10.1016/bs.acc.2018.06.001

[17] Dudek, Piotr et al. “Late-onset hypogonadism.” Przeglad menopauzalny = Menopause review vol. 16,2 (2017): 66-69. doi:10.5114/pm.2017.68595

[18] Yim, Jeong Yoon et al. “Serum testosterone and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in men and women in the US.” Liver international: official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver vol. 38,11 (2018): 2051-2059. doi:10.1111/liv.13735

[19] Mulligan, T et al. “Prevalence of hypogonadism in males aged at least 45 years: the HIM study.” International journal of clinical practice vol. 60,7 (2006): 762-9. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.00992.x

[20] Decaroli, Maria Chiara, and Vincenzo Rochira. “Aging and sex hormones in males.” Virulence vol. 8,5 (2017): 545-570. doi:10.1080/21505594.2016.1259053

[21] Singh, Parminder. “Andropause: Current concepts.” Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism vol. 17,Suppl 3 (2013): S621-9. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.123552.

[22] Swee, Du Soon, and Earn H Gan. “Late-Onset Hypogonadism as Primary Testicular Failure.” Frontiers in endocrinology vol. 10 372. 12 Jun. 2019, doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00372

[xxiii] Giagulli, Vito Angelo et al. “Critical evaluation of different available guidelines for late-onset hypogonadism.” Andrology vol. 8,6 (2020): 1628-1641. doi:10.1111/andr.12850

[xxiv] Jakiel, Grzegorz et al. “Andropause - state of the art 2015 and review of selected aspects.” Przeglad menopauzalny = Menopause review vol. 14,1 (2015): 1-6. doi:10.5114/pm.2015.49998