Welcome to part 2 of the ODX Menopause Series. In this post, the ODX Research team reviews the biology and physiology of menopause, its identifiable phases, and what lifestyle factors can affect it.

The ODX Menopause Series

- Menopause Part 1: A Quick Overview of a Slow Process

- Menopause Part 2: Biology and Physiology of Menopause

- Menopause Part 3: Increased Risk of Disease Associated with Menopause

- Menopause Part 4: Identifying Menopause: Signs and Symptoms

- Menopause Part 5: Laboratory Evaluation of Menopause

- Menopause Part 6: Cardiovascular Risk in Menopause

- Menopause Part 7: Beyond Hormone Testing in Menopause

- Menopause Part 8: Natural Approaches to Menopause

- Menopause Part 9: Diet and Nutrition Intervention in Menopause

- Menopause Part 10: Characteristic of Herbal Derivatives used to Alleviate Menopause Symptoms

- Menopause Part 11: Lifestyle Approaches to Menopause

- Menopause Part 12: The National Institute on Aging Addresses Hot Flashes

- Menopause Part 13: Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) in Menopause

- Menopause Part 14: North American and European Guidelines for Hormonal Management of Menopause

- Menopause Part 15: Bioidentical Hormone Therapy

- Menopause Part 16: Optimal Takeaways for Menopause

- Optimal The Podcast - Episode 10

Menopause occurs once ovaries become depleted of oocytes (immature eggs) and the cyclical pattern of hormones and peptides ceases. The significant decrease in estrogen, especially estradiol, can contribute to unpleasant symptoms and physiological consequences. Decreased progesterone also contributes to symptomatology.

Although ovarian production of steroid hormones declines after menopause, estrogens can still be produced elsewhere including adipose tissue, and higher estrogen levels can be seen in obesity. Steroid hormones can also be produced from dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in significant amounts in a process called intracrinology.[1]

However, as the use of LDL cholesterol for estrogen production in the ovaries decreases, circulating LDL cholesterol increases, characterizing the dyslipidemia associated with menopause.[2] Within one year of menopause, total and LDL-cholesterol and apolipoprotein B can become substantially elevated.[3]

Menopause can occur at an earlier than expected age due to a phenomenon known as premature ovarian failure (POF). Researchers note that POF can be triggered by[4]

- Chromosomal disorders, e.g., Fragile X syndrome, Turner syndrome

- Eating disorders

- Environmental pollution

- Excessive exercise

- Genetic disorders

- Medications for fibroids or endometriosis

- Obesity

- Stress

Early menopause may also be brought on by removal of both ovaries (bilateral oophorectomy), radiation, chemotherapy, or analogues of gonadotrophin-releasing hormones.[5]

The age at which menopause occurs is influenced by[6]

- Alcohol use

- Diet

- Eating disorders

- Education

- Employment

- Ethnicity

- Exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals

- Oral contraceptive use

- Physical activity

- Smoking

- Weight

Menopause occurs in phases

Initial observations include:[7]

- Premenopause: No cycle changes, menses occurred within 3 months

- Early perimenopause: Less predictable cycles, menses within last 3 months

- Late perimenopause: No menses for 3-11 months

- Postmenopause: 12 consecutive months of amenorrhea (no menses)

- Early postmenopause: 24 or fewer months since date of final menstruation

- Late postmenopause: Greater than 24 months since final menstruation

The 2011 update to WHO Stages of Reproductive Aging workshop known as STRAW +10 further defines stages and characteristics of menopause for women over age 40.[8]

Perimenopause (menopausal transition and early postmenopause):

Early menopausal transition:

-

- 7 or greater day difference in length of consecutive cycles

- Variable duration

Late menopausal transition:

-

- Intervals of no menses (amenorrhea) 60 or more days per interval

- May last 1-3 years

Postmenopause

Early postmenopause

-

- 2-6 years

Late postmenopause

-

- Remaining lifespan

Estrogen and Progesterone

There are four types of estrogen: estrone (E1), estradiol (E2), estriol (E3), and estetrol (E4), with estradiol being the most abundant and the most potent. When ovarian production of estradiol decreases with menopause, other tissues are able to synthesize it, including adipose tissue, bone, brain, and smooth muscle cells of the vascular endothelium.[9] In fact, estrogen receptors are found in non-reproductive tissues including adipose tissue, liver, skeletal muscle, and the central nervous system, highlighting its importance in metabolism.[10]

Several functions in the body are regulated by estrogen and progesterone and these functions will be affected when circulating hormone levels fluctuate:[11] [12] [13]

|

Estrogens regulate |

Progesterone regulates |

|

|

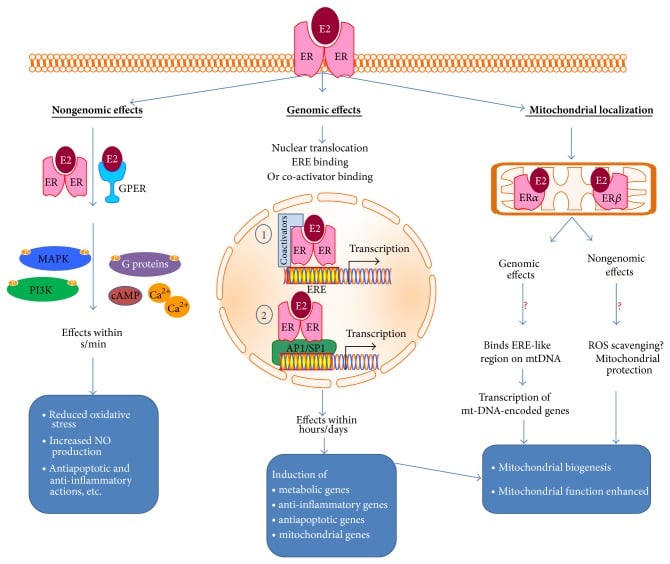

Mechanisms of Estrogen Action

Source: Gupte, Anisha A et al. “Estrogen: an emerging regulator of insulin action and mitochondrial function.” Journal of diabetes research vol. 2015 (2015): 916585. doi:10.1155/2015/916585 This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License.

References

[1] Honour, John W. “Biochemistry of the menopause.” Annals of clinical biochemistry vol. 55,1 (2018): 18-33. doi:10.1177/0004563217739930

[2] Ko, Seong-Hee, and Hyun-Sook Kim. “Menopause-Associated Lipid Metabolic Disorders and Foods Beneficial for Postmenopausal Women.” Nutrients vol. 12,1 202. 13 Jan. 2020, doi:10.3390/nu12010202

[3] Barańska, Agnieszka et al. “Effects of Soy Protein Containing of Isoflavones and Isoflavones Extract on Plasma Lipid Profile in Postmenopausal Women as a Potential Prevention Factor in Cardiovascular Diseases: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.” Nutrients vol. 13,8 2531. 24 Jul. 2021, doi:10.3390/nu13082531 [R}

[4] Honour, John W. “Biochemistry of the menopause.” Annals of clinical biochemistry vol. 55,1 (2018): 18-33. doi:10.1177/0004563217739930

[5] Neves-E-Castro, Manuel et al. “EMAS position statement: The ten point guide to the integral management of menopausal health.” Maturitas vol. 81,1 (2015): 88-92. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.02.003

[6] Honour, John W. “Biochemistry of the menopause.” Annals of clinical biochemistry vol. 55,1 (2018): 18-33. doi:10.1177/0004563217739930

[7] Derby, Carol A et al. “Lipid changes during the menopause transition in relation to age and weight: the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation.” American journal of epidemiology vol. 169,11 (2009): 1352-61. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp043

[8] Harlow, Siobán D et al. “Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging.” Menopause (New York, N.Y.) vol. 19,4 (2012): 387-95. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e31824d8f40

[9] Hariri, Lana. and Anis Rehman. “Estradiol.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 13 February 2021. This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (),

[10] Marchand, Geneviève B et al. “Increased body fat mass explains the positive association between circulating estradiol and insulin resistance in postmenopausal women.” American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism vol. 314,5 (2018): E448-E456. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00293.2017

[11] Honour, John W. “Biochemistry of the menopause.” Annals of clinical biochemistry vol. 55,1 (2018): 18-33. doi:10.1177/0004563217739930

[12] Gupte, Anisha A et al. “Estrogen: an emerging regulator of insulin action and mitochondrial function.” Journal of diabetes research vol. 2015 (2015): 916585. doi:10.1155/2015/916585

[13] Hariri, Lana. and Anis Rehman. “Estradiol.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 13 February 2021. This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (),