Welcome to part 11 of the ODX Inflammation Series. In this post, the ODX Research Team reviews the ways we can treat inflammation using an anti-inflammatory diet.

Remember that inflammation serves a purpose, including killing off pathogens and clearing away damaged tissue and debris. However, resolution of inflammation is the key to healing and recovery.

Inflammation can be dampened down with anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and IL-37; with IL-1 and TNF receptors acting as “decoys;” and via the presence of endogenous corticosteroids and catecholamines. [1]

However, recall that impairing IL-6 classic signaling and allowing prolonged immunoparalysis can be detrimental.

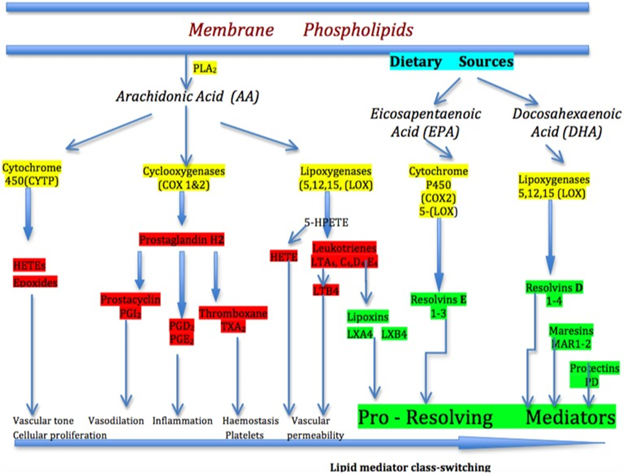

The arachidonic acid (AA) pathway of inflammation mediators. In the simplified pathway for the eicosanoid metabolic pathway, AA is released from membrane stores by phospholipase 2 (PLA2). AA is metabolized to biological mediators by three enzymatic pathways: cyclooxygenase, lipoxygenase, and cytochrome P450. Each pathway contains enzyme-specific steps that result in a wide variety of bioactive compounds that drive the pro-inflammatory (prostaglandins) response. After lipid mediator class-switching at the height of inflammation, the pro-resolving mediators-lipoxins begin to drive inflammation resolution. Eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid-derived from dietary sources produce the E-series of resolvins and D-series of resolvins, maresins, and protectins, respectively, which are important pro-resolving mediators in progressing the resolution of inflammation.

Source: Rea, Irene Maeve et al. “Age and Age-Related Diseases: Role of Inflammation Triggers and Cytokines.” Frontiers in immunology vol. 9 586. 9 Apr. 2018, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).

It should come as no surprise that a diet based on a wide variety of fresh whole foods is rich in micronutrients and anti-inflammatory compounds. On the other obvious hand, a pro-inflammatory diet based on processed food and “fast food” is laden with pro-inflammatory compounds and inherently deficient in micronutrients.

Anti-inflammatory |

Pro-inflammatory |

|

Whole fresh foods |

Processed convenience foods |

|

Abundant fresh fruits and vegetables, at least 7-9 servings per day including dark leafy greens, cruciferous vegetables, citrus fruits |

Low in fruits in vegetables, fewer than 5 servings per day |

|

Low in refined carbohydrates including white bread, cookies, cake, pastry, most candy, sweetened beverages, etc. Moderate amounts of whole grain products. |

High in refined carbohydrates, added sugar, sweetened beverages, etc. Low in whole grain products.

|

|

Abundance of lean protein sources including grass-fed beef, chicken, seafood, omega-3 eggs, intake of high-omega-3 (low mercury) fish or purified fish oil 2-3 times per week. |

High in processed meats, fatty red meat sources |

|

Healthy sources of fat including nuts, seeds, avocados, olives, olive oil, limited amounts of organic grass-fed butter |

High in unhealthy fats including vegetable oils, margarine, hydrogenated oils, deep fried foods, trans fats |

|

High in omega-3 fatty acids including alpha-linolenic acid, EPA, DHA |

Low in omega-3 fats |

|

Limited in omega-6 fats (though still need a source of essential omega-6 alpha linoleic acid) |

High in omega-6 fatty acids, especially from vegetables oils and animal-based fats |

|

Limited saturated fat (especially animal-based) |

Excess animal-based fats |

|

No trans fats from industrial sources |

High in trans fats from industrial sources including hydrogenated oils and deep fried foods |

|

Abundance of herbs and spices with anti-inflammatory sources including turmeric, ginger, rosemary, curry blends |

Low in herbs and spices, high in excess salt |

Researchers observe that a Western-style diet is associated with non-communicable chronic disease and metaflammation (metabolic inflammation). It is often accompanied by a variety of factors related to suboptimal health including [8]

An underlying link between diet and inflammation is the fact that dietary constituents can have pro- and anti-inflammatory effects. [9]

Researchers scored and indexed a sample of 45 foods for inflammatory potential based on well-known inflammatory markers: IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and C-reactive protein.

Research revealed that a pro-inflammatory diet was associated with elevated serum levels of hs-CRP, IL-6, and TNF-alpha. [10]

Within the DII, values were assigned to the foods studied to reflect inflammatory potential:

Fast food diet: +4.07

Mediterranean diet: -3.96

Macrobiotic diet -5.54

Highlights of an anti-inflammatory diet include an abundance of fresh fruits and vegetables, herbs and spices, omega-3 sources, and minimally processed foods.

Omega-3 fatty acids exert anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-alpha. Excess omega-6 linoleic acid, on the other hand, promotes inflammation, platelet aggregation, and oxidation of LDL. [11]

Many herbs and spices are incorporated into traditional diets for flavor, but also for their anti-inflammatory properties. Herbs and spices tend to be scarce in the Western diet.

Studies have been conducted in an LPS-stimulated macrophage model revealing that various herbs, spices, and fruits exhibited anti-inflammatory effects by reducing IL-6 or TNF-alpha, enhancing IL-10 production, or by reducing COX-2 or iNOS. The most significant effects of these tested were seen with allspice, basil, bay leaves, black pepper, chili pepper, licorice, nutmeg, oregano, sage, and thyme. Increasing intake of foods rich in anti-inflammatory compounds and antioxidants can not only reduce risk of cancer but of neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. [14]

Curcumin, an active constituent of the spice turmeric, appears to exert anti-inflammatory effects in humans, possibly via its ability to enhance IL-10 action, scavenge free radicals, enhance antioxidant activity, and influence signaling pathways. [15] [16]

Flavonoids from plant-based foods (fruits, vegetables, grains, roots, tea, wine), honey, and propolis provide a number of health benefits including anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory actions. [17]

It is important to remember that some natural supplements that may “boost” immunity could theoretically exacerbate an already heightened immune system. These compounds include echinacea purpura, garlic extracts, astragalus, and Andrographis. [18]

So, our optimal takeaways for inflammation with a focus on cytokines include:

[1] Rea, Irene Maeve et al. “Age and Age-Related Diseases: Role of Inflammation Triggers and Cytokines.” Frontiers in immunology vol. 9 586. 9 Apr. 2018,.

[2] Mahan, L. Kathleen; Raymond, Janice L. Krause's Food & the Nutrition Care Process - E-Book (Krause's Food & Nutrition Therapy). Elsevier Health Sciences. Kindle Edition.

[3] Weil Anti-inflammatory diet. https://www.drweil.com/diet-nutrition/anti-inflammatory-diet-pyramid/dr-weils-anti-inflammatory-food-pyramid/

[4] Mediterranean diet. Oldways. https://oldwayspt.org/resources/oldways-mediterranean-diet-pyramid

[5] Sears, Barry. “Anti-inflammatory Diets.” Journal of the American College of Nutrition vol. 34 Suppl 1 (2015): 14-21.

[6] Institute for Natural Medicine. https://naturemed.org/what-is-an-anti-inflammatory-diet/

[7] Rupp, Heinz et al. “Risk stratification by the "EPA+DHA level" and the "EPA/AA ratio" focus on anti-inflammatory and antiarrhythmogenic effects of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids.” Herz vol. 29,7 (2004): 673-85. doi:10.1007/s00059-004-2602-4 [R]

[8] Christ, Anette et al. “Western Diet and the Immune System: An Inflammatory Connection.” Immunity vol. 51,5 (2019): 794-811. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2019.09.020 [R] [R]

[9] Steck, S. E. S. N., et al. "The dietary inflammatory index: a new tool for assessing diet quality based on inflammatory potential." Digest 49.3 (2014): 1-10. [R] [R]

[10] Steck, S. E. S. N., et al. "The dietary inflammatory index: a new tool for assessing diet quality based on inflammatory potential." Digest 49.3 (2014): 1-10. [R] [R]

[11] Simopoulos, Artemis P. “The omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio, genetic variation, and cardiovascular disease.” Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition vol. 17 Suppl 1 (2008): 131-4. [R]

[12] Rea, Irene Maeve et al. “Age and Age-Related Diseases: Role of Inflammation Triggers and Cytokines.” Frontiers in immunology vol. 9 586. 9 Apr. 2018, doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00586 [R] This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).

[13] Wall, Rebecca et al. “Fatty acids from fish: the anti-inflammatory potential of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids.” Nutrition reviews vol. 68,5 (2010): 280-9. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00287.x [R]

[14] Mueller, Monika, Stefanie Hobiger, and Alois Jungbauer. "Anti-inflammatory activity of extracts from fruits, herbs and spices." Food Chemistry 122 (2010): 987-996 [R]

[15] Mollazadeh, Hamid et al. “Immune modulation by curcumin: The role of interleukin-10.” Critical reviews in food science and nutrition vol. 59,1 (2019): 89-101. doi:10.1080/10408398.2017.1358139 [R] [R]

[16] Hunter, Philip. “The inflammation theory of disease. The growing realization that chronic inflammation is crucial in many diseases opens new avenues for treatment.” EMBO reports vol. 13,11 (2012): 968-70. doi:10.1038/embor.2012.142 [R]

[17] Zeinali, Majid et al. “An overview on immunoregulatory and anti-inflammatory properties of chrysin and flavonoids substances.” Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie vol. 92 (2017): 998-1009. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2017.06.003 [R] [R]

[18] Young, Trevor K, and John G Zampella. “Supplements for COVID-19: A modifiable environmental risk.” Clinical immunology (Orlando, Fla.) vol. 216 (2020): 108465. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2020.108465 [R] Elsevier hereby grants permission to make all its COVID-19-related research that is available on the COVID-19 resource centre - including this research content

[19] Rea, Irene Maeve et al. “Age and Age-Related Diseases: Role of Inflammation Triggers and Cytokines.” Frontiers in immunology vol. 9 586. 9 Apr. 2018, doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00586 [R] This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).

[20] Korniluk, A et al. “From inflammation to cancer.” Irish journal of medical science vol. 186,1 (2017): 57-62. doi:10.1007/s11845-016-1464-0 [R]

[21] Stone, William L., et al. “Pathology, Inflammation.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 27 August 2020. [R]

[22] Dinarello, Charles A. “Overview of the IL-1 family in innate inflammation and acquired immunity.” Immunological reviews vol. 281,1 (2018): 8-27. doi:10.1111/imr.12621 [R]

[23] Rose-John, Stefan. “Interleukin-6 Family Cytokines.” Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology vol. 10,2 a028415. 1 Feb. 2018.

[24] Schett, Georg et al. “How cytokine networks fuel inflammation: Toward a cytokine-based disease taxonomy.” Nature medicine vol. 19,7 (2013): 822-4.

[25] Clendenen, Tess V et al. “Factors associated with inflammation markers, a cross-sectional analysis.” Cytokine vol. 56,3 (2011): 769-78.

[26] Garbers, Christoph et al. “Plasticity and cross-talk of interleukin 6-type cytokines.” Cytokine & growth factor reviews vol. 23,3 (2012): 85-97.

[27] Barnes, Theresa C et al. “The many faces of interleukin-6: the role of IL-6 in inflammation, vasculopathy, and fibrosis in systemic sclerosis.” International journal of rheumatology vol. 2011 (2011): 721608.

[28] Hartman, Joshua, and William H Frishman. “Inflammation and atherosclerosis: a review of the role of interleukin-6 in the development of atherosclerosis and the potential for targeted drug therapy.” Cardiology in review vol. 22,3 (2014): 147-51.

[29] Spooren, Anneleen et al. “Interleukin-6, a mental cytokine.” Brain research reviews vol. 67,1-2 (2011): 157-83.

[30] Munkholm, Klaus et al. “Cytokines in bipolar disorder vs. healthy control subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Journal of psychiatric research vol. 47,9 (2013): 1119-33.

[31] Valkanova, Vyara et al. “CRP, IL-6 and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies.” Journal of affective disorders vol. 150,3 (2013): 736-44.

[32] Candido, Juliana, and Thorsten Hagemann. “Cancer-related inflammation.” Journal of clinical immunology vol. 33 Suppl 1 (2013): S79-84.

[33] Lippitz, Bodo E. “Cytokine patterns in patients with cancer: a systematic review.” The Lancet. Oncology vol. 14,6 (2013): e218-28.

[34] Astrom, Maj-Briit et al. “Persistent low-grade inflammation and regular exercise.” Frontiers in bioscience (Scholar edition) vol. 2 96-105. 1 Jan. 2010,

[35] Suzuki, Katsuhiko. "Cytokine response to exercise and its modulation." Antioxidants 7.1 (2018): 17.

[36] Suzuki, Katsuhiko et al. “Systemic inflammatory response to exhaustive exercise. Cytokine kinetics.” Exercise immunology review vol. 8 (2002): 6-48.

[37] Munasinghe, Lalani L et al. “The association of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations with elevated serum ferritin levels in normal weight, overweight and obese Canadians.” PloS one vol. 14,3 e0213260. 7 Mar. 2019.

[38] Kappert, Kai et al. “Assessment of serum ferritin as a biomarker in COVID-19: bystander or participant? Insights by comparison with other infectious and non-infectious diseases.” Biomarkers : biochemical indicators of exposure, response, and susceptibility to chemicals, 1-36. 23 Jul. 2020.

[39] Mehta, Puja et al. “COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression.” Lancet (London, England) vol. 395,10229 (2020): 1033-1034.

[40] Sinha, Pratik et al. “Is a "Cytokine Storm" Relevant to COVID-19?.” JAMA internal medicine vol. 180,9 (2020): 1152-1154.

[41] Cena, Hellas, and Marcello Chieppa. “Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19-SARS-CoV-2) and Nutrition: Is Infection in Italy Suggesting a Connection?.” Frontiers in immunology vol. 11 944. 7 May. 2020.

[42] Panickar, Kiran S, and Dennis E Jewell. “The beneficial role of anti-inflammatory dietary ingredients in attenuating markers of chronic low-grade inflammation in aging.” Hormone molecular biology and clinical investigation vol. 23,2 (2015): 59-70.

[43] Shirani, Fatemeh, Farzin Khorvash, and Arman Arab. "Review on selected potential nutritional intervention for treatment and prevention of viral infections: possibility of recommending these for Coronavirus 2019." International Journal of Food Properties 23.1 (2020): 1722-1736.