Endothelial Dysfunction – Functional Naturopathic Approach

Dicken Weatherby, N.D. and Beth Ellen DiLuglio, MS, RDN, LDN

Allopathic approaches to endothelial dysfunction are based on its identification once established versus early prevention. Functional approaches to endothelial dysfunction rely on recognition of contributing factors and early assessment of related biomarkers.

The Endothelial Dysfunction Series

- Endothelial Dysfunction part 1 - An Overview

- Endothelial Dysfunction part 2 - The Endothelium

- Endothelial Dysfunction part 3 - Nitric Oxide

- Endothelial Dysfunction part 4 - Diseases and Causes

- Endothelial Dysfunction part 5 - Immune Response & Oxidative Stress

- Endothelial Dysfunction part 6 - Atherosclerosis

- Endothelial Dysfunction part 7 - Assessment Part 1

- Endothelial Dysfunction part 8 - Assessment part 2

- Endothelial Dysfunction part 9 - Functional Naturopathic Approach

- Endothelial Dysfunction part 10 - Optimal Takeaways

Allopathic Approach to Treatment

- A number of pharmaceutical interventions have been researched including eNOS enhancers, nitrate therapy, alpha-beta blockers for blood pressure management, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors to treat high blood pressure and heart failure, statins, novel therapies (e.g. ranolazine, aminophylline).[1] [2] Interestingly, it is the antioxidant function of some of these pharmaceuticals that protect the endothelium.

- Bradykinin and acetylcholine can be administered to stimulate NO synthesis, while nitroglycerine and sodium nitroprusside can be converted to nitric oxide.[3]

- External counter pulsation (ECP) therapy may be used to help supply oxygen-rich blood to the heart.[4]

- The NSAID indomethacin (as well as vitamin C) was found to reverse the blunted vasodilation response to acetylcholine by restoring bioavailability of nitric oxide.

Functional Naturopathic Approach

Functional approaches to endothelial dysfunction rely on recognition of contributing factors and early assessment of related biomarkers.

Early stages of endothelial dysfunction may be reversible before full progression to atherosclerosis.[5]

Major modifiable factors contributing to endothelial dysfunction include unhealthy diet (inflammatory, processed foods, low in micronutrients, antioxidants, phytonutrients, fiber, omega-3s, monounsaturated fats); exposure to cigarette smoke, toxins, and pollution; excess inflammatory compounds and oxidative stress; nutrient insufficiencies; and sedentary lifestyle. Assessing these factors should be the first step in evaluating risk of atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction.

Remember, unbridled oxidative stress and inflammation disrupt nitric oxide metabolism and promote endothelial dysfunction. They must be addressed to order to rein in this potentially debilitating condition:[6]

It is likely that excess inflammation from any source, even periodontitis or arthritis, can cause damage to the vascular endothelium so a full history is essential.[7]

The functional, naturopathic approach to endothelial dysfunction is recognition of its causes and mitigation of their effects. Early recognition of oxidative stress risk and detection of endothelial dysfunction is critical to reversing or preventing atherosclerosis and its progression to CVD.[8]

|

Source: Widmer, R Jay, and Amir Lerman. “Endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular disease.” Global cardiology science & practice vol. 2014,3 291-308. 16 Oct. 2014, doi:10.5339/gcsp.2014.43 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution license CC BY 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

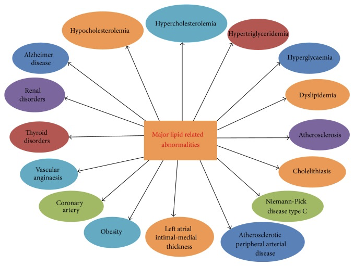

Source: Upadhyay, Ravi Kant. “Emerging risk biomarkers in cardiovascular diseases and disorders.” Journal of lipids vol. 2015 (2015): 971453. doi:10.1155/2015/971453 This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Continued exposure to cardiovascular risk factors is mirrored in pathological changes to blood vessels. Loss of integrity of the vascular endothelium is accompanied by increased smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation, leukocyte migration, and adhesion.[9]

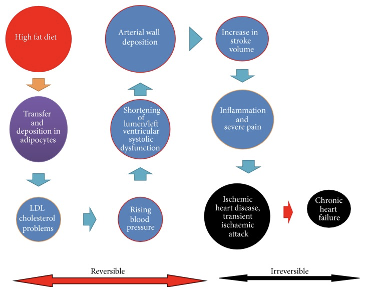

Successive progression of transient ischemic attack and chronic heart failure in man.

Source: Upadhyay, Ravi Kant. “Emerging risk biomarkers in cardiovascular diseases and disorders.” Journal of lipids vol. 2015 (2015): 971453. doi:10.1155/2015/971453 This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Negative effects of a high-fat diet

Meta-analysis indicates that endothelial function is typically compromised in adults following a high-fat mixed meal and that the observed impairment in brachial artery flow-mediated dilation is a sign of cardiovascular risk, morbidity and mortality. Researchers investigated whether adolescents would demonstrate similar changes in post-prandial flow mediated dilation.

A small study of 10 adolescents observed that a high-fat meal also high in protein did not significantly impair arterial dilation in the same way a high-fat diet was expected to. Also, addition of insoluble wheat fiber to a high-fat meal blunted post-prandial hypertriglyceridemia and related changes in flow-mediated arterial dilation. Researchers recommend conducting larger studies to investigate these relationships further.[10]

A high-fat Western-style diet can impair endothelial function for up to four hours. To investigate mitigation of this threat, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of phytonutrient supplementation in 38 healthy adult volunteers was conducted.

Results indicated that daily supplementation with fruit and vegetable concentrates, including those enhanced with antioxidant nutrients, significantly improved flow-mediated vasodilation using the brachial artery reactivity test (BART) following a high-fat fast food meal containing 50 grams of fat.

In the supplement group, serum total and LDL cholesterol decreased significantly, and serum levels of nitric oxide metabolites increased significantly.[11]

This study followed up the observation that supplementation with antioxidants vitamin C and vitamin E prevented the significant reduction in vasodilation that occurs following a high-fat meal.[12]

A healthy plant-based diet and healthy lifestyle are preventive

Phytonutrients/phytochemicals are compounds unique to plant-based foods. Many of them have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory benefits.

Abundant intake of fruits, vegetables, phytonutrients, and antioxidants is closely associated with optimal health, including reduction of cardiovascular risk factors. Research demonstrates that phytonutrients and antioxidants can exert positive effects on endothelial function, including its generation of nitric oxide. These positive effects are not new news, they just seem to have been forgotten in the medical models that have been developed.

Omega-3 fatty acids can have a vasoprotective effect in endothelial dysfunction as demonstrated in a number of studies in those with metabolic syndrome, elevated BMI, hyperlipidemia, and those who smoked cigarettes. A benefit of omega-3 intake in in diabetics was also observed in two of five studies reviewed. Specific vasoprotective effects of omega-3 fatty acids include:[13]

- Anti-inflammatory activity

- Decreased blood pressure

- Improved vasodilation as measured by FMD

- Increased antioxidant protection

Naturally occurring antioxidants can have important protective effects against endothelial dysfunction: [14]

N-acetylcysteine (NAC)

- Has potent antioxidant effects

- Essential to synthesis of glutathione

- Inhibits inflammatory cytokine release, NADPH oxidase expression, and white blood cell adhesion

- Improves endothelial response with and without presence of atherosclerosis

Vitamin C

- Scavenges superoxide, therefore preventing lipid peroxidation, platelet/neutrophil activation, adhesion molecule upregulation, and scavenging of NO

- Scavenges reactive nitrogen species, inhibits LDL oxidation

- Can improve endothelium response in diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, smoking

- The lowest measured tertile of vitamin C in a study of type 1 diabetics 0.25 – 0.86 mg/dL (14.02-49.01 umol/L) versus the highest tertile 1.48-2.10 mg/dL (84.01 to 118.99 umol/L) was significantly associated with greater carotid intima-media thickness, a presumed sign of atherosclerosis.[15]

- Administration of vitamin C restored nitric oxide bioavailability and reversed a blunted vasodilation response to acetylcholine.[16]

Vitamin E

- Scavenges hydroperoxyl radicals as a lipid-soluble antioxidant

- Protects endothelial function in hypercholesterolemia and smoking

Supplementation

Adherence to a healthy diet is essential to addressing atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction. However, supplementation may be beneficial as well, especially considering that micronutrient deficiencies are common among the general population but even more common in those with hypertension, cardiovascular disease, environmental toxin exposure, and prescription drug use.[17]

Nutrition supplementation can significantly improve endothelial function as evidenced by a number of clinical studies.

Vitamin C

Vitamin C (ascorbate/ascorbic acid) is of particular interest due to its potent antioxidant activity as a free radical scavenger and the fact that humans cannot synthesize ascorbate while most mammals can.

- Vitamin C is required for the function and optimal permeability of the endothelium and its insufficiency is noted as a cause of endothelial dysfunction.[18]

- A small prospective study indicated that daily antioxidant supplementation with 1 gram of vitamin C and 500 mg of vitamin E significantly improve endothelial function as evidenced by restoration of flow-mediated dilation. Beneficial effects disappeared 1 month after supplementation ceased.[19]

- Vitamin C (1 gram/day) and vitamin E (440 IU/day) significantly improved FMD in adult male hypertensive patients as evidenced in a randomized double-blind study.[20]

- Supplementation with vitamin C (500 mg/day) and vitamin E (400 IU/day) also significantly improved endothelial function and FMD in a randomized double-blind study of children with hyperlipidemia 9-20 years of age.[21]

Arginine

Arginine supplementation may also be of specific benefit in endothelial dysfunction.

- Administration of arginine was found to improve endothelial dysfunction in subjects with high cholesterol and atherosclerosis.[22] [23]

- L- arginine, applied intravenously or via intracoronary administration improved endothelium-dependent vasodilation in such patients. The D-arginine form is not effective.[24]

- Intervention with arginine and vitamins B6, B12, and folic acid significantly improved vascular function in 40 individuals with moderately elevated blood pressure. Homocysteine and systolic blood pressure were significantly reduced in this randomized double-blind study as well.[25]

A variety of nutrients are found to have antihypertensive effects, therefore reducing stress and further damage to the vascular endothelium. These include: [26]

- Alpha lipoic acid

- Calcium

- CoQ10

- Flavonoids

- Gamma-linolenic acid

- Garlic

- L-carnitine

- Magnesium

- Melatonin

- Monounsaturated fats

- N-acetylcysteine

- Omega-3 fatty acids alpha linolenic acid, EPA, DHA

- Pomegranate

- Potassium

- Pycnogenol

- Resveratrol

- Taurine

- Vitamin B6

- Vitamin C

- Vitamin D

- Vitamin E, gamma/delta tocopherols, tocotrienols

- Zinc

Coenzyme Q10

Coenzyme Q10 is produced endogenously though its production is impaired by HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statin drugs). Supplementation with 150 mg of CoQ10 per day can support antioxidant function, reduce inflammatory IL-6, and reduce oxidative stress in those with coronary artery disease.[27]

Melatonin

A randomized, double-blind, controlled study of 20 individuals with advanced atherosclerosis and CAD indicated that supplementation with 10 mg of melatonin was associated with a significant decrease in mean levels of ICAM, VCAM, and CRP, and a significant increase in nitric oxide.[28]

Vitamin B12

Preliminary research suggests a role for cobalamin as a cofactor in the metabolism of nitric oxide. Researchers propose that the intermediate glutathionyl-cobalamin is an active form of B12 that participates in production and function of nitric oxide and in turn effects cell membrane protection, immune, and vascular health.[29]

Pomegranate

A meta-analysis of 16 studies indicated that supplementation with pomegranate juice had a significant effect on inflammatory markers hs-CRP, IL-6, and TNF-alpha.[30]

Dark Chocolate

Dark chocolate (high in flavonoids and antioxidant factors) significantly improved endothelial-dependent coronary vascular function, reduced oxidative stress, and reduced platelet adhesion in 22 heart transplant patients.[31]

Physical Activity

Though a topic unto itself, physical activity and exercise can improve endothelial function… no surprise there![32]

Animal and human research support the application of regular, robust physical activity to support cardiovascular and endothelial function. A minimum of 40 minutes of physical activity at least 3 days per week is recommended. Optimal activity includes 10,000 steps per day and engagement in aerobic activity 3 days per week.[33]

NEXT UP - Endothelial Dysfunction part 10 - The Optimal Takeaways

Research

[1] Su, Jin Bo. “Vascular endothelial dysfunction and pharmacological treatment.” World journal of cardiology vol. 7,11 (2015): 719-41.

[2] Hirata, Yasunobu et al. “Diagnosis and treatment of endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease.” International heart journal vol. 51,1 (2010): 1-6.

[3] Miller, Mark R. “Oxidative stress and the cardiovascular effects of air pollution.” Free radical biology & medicine vol. 151 (2020): 69-87.

[4] Cedars Sinai Women’s Heart Center. Endothelial Function Testing

[5] Park, Kyoung-Ha, and Woo Jung Park. “Endothelial Dysfunction: Clinical Implications in Cardiovascular Disease and Therapeutic Approaches.” Journal of Korean medical science vol. 30,9 (2015): 1213-25.

[6] Widmer, R Jay, and Amir Lerman. “Endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular disease.” Global cardiology science & practice vol. 2014,3 291-308. 16 Oct. 2014.

[7] Stone, William L., et al. “Pathology, Inflammation.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 27 August 2020.

[8] Park, Kyoung-Ha, and Woo Jung Park. “Endothelial Dysfunction: Clinical Implications in Cardiovascular Disease and Therapeutic Approaches.” Journal of Korean medical science vol. 30,9 (2015): 1213-25.

[9] Park, Kyoung-Ha, and Woo Jung Park. “Endothelial Dysfunction: Clinical Implications in Cardiovascular Disease and Therapeutic Approaches.” Journal of Korean medical science vol. 30,9 (2015): 1213-25.

[10] Whisner, Corrie M et al. “Effects of Low-Fat and High-Fat Meals, with and without Dietary Fiber, on Postprandial Endothelial Function, Triglyceridemia, and Glycemia in Adolescents.” Nutrients vol. 11,11 2626. 2 Nov. 2019.

[11] Plotnick, Gary D et al. “Effect of supplemental phytonutrients on impairment of the flow-mediated brachial artery vasoactivity after a single high-fat meal.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology vol. 41,10 (2003): 1744-9.

[12] Plotnick, G D et al. “Effect of antioxidant vitamins on the transient impairment of endothelium-dependent brachial artery vasoactivity following a single high-fat meal.” JAMA vol. 278,20 (1997): 1682-6.

[13] Zehr, Kayla R, and Mary K Walker. “Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids improve endothelial function in humans at risk for atherosclerosis: A review.” Prostaglandins & other lipid mediators vol. 134 (2018): 131-140.

[14] Su, Jin Bo. “Vascular endothelial dysfunction and pharmacological treatment.” World journal of cardiology vol. 7,11 (2015): 719-41.

[15] Odermarsky, Michal et al. “Poor vitamin C status is associated with increased carotid intima-media thickness, decreased microvascular function, and delayed myocardial repolarization in young patients with type 1 diabetes.” The American journal of clinical nutrition vol. 90,2 (2009): 447-52.

[16] Virdis, Agostino et al. “Human endothelial dysfunction: EDCFs.” Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology vol. 459,6 (2010): 1015-23.

[17] Houston, Mark. “The role of nutrition and nutraceutical supplements in the treatment of hypertension.” World journal of cardiology vol. 6,2 (2014): 38-66.

[18] May, James M, and Fiona E Harrison. “Role of vitamin C in the function of the vascular endothelium.” Antioxidants & redox signaling vol. 19,17 (2013): 2068-83.

[19] Takase, Bonpei et al. “Effect of chronic oral supplementation with vitamins on the endothelial function in chronic smokers.” Angiology vol. 55,6 (2004): 653-60.

[20] Plantinga, Yvonne et al. “Supplementation with vitamins C and E improves arterial stiffness and endothelial function in essential hypertensive patients.” American journal of hypertension vol. 20,4 (2007): 392-7.

[21] Engler, Marguerite M et al. “Antioxidant vitamins C and E improve endothelial function in children with hyperlipidemia: Endothelial Assessment of Risk from Lipids in Youth (EARLY) Trial.” Circulation vol. 108,9 (2003): 1059-63.

[22] Gornik, Heather L, and Mark A Creager. “Arginine and endothelial and vascular health.” The Journal of nutrition vol. 134,10 Suppl (2004): 2880S-2887S; discussion 2895S.

[23] Morris, Sidney M Jr. “Arginine: beyond protein.” The American journal of clinical nutrition vol. 83,2 (2006): 508S-512S.

[24] Widmer, R Jay, and Amir Lerman. “Endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular disease.” Global cardiology science & practice vol. 2014,3 291-308. 16 Oct. 2014.

[25] Menzel, Daniel et al. “L-Arginine and B vitamins improve endothelial function in subjects with mild to moderate blood pressure elevation.” European journal of nutrition vol. 57,2 (2018): 557-568.

[26] Houston, Mark. “The role of nutrition and nutraceutical supplements in the treatment of hypertension.” World journal of cardiology vol. 6,2 (2014): 38-66.

[27] Bronzato, Sofia, and Alessandro Durante. “Dietary Supplements and Cardiovascular Diseases.” International journal of preventive medicine vol. 9 80. 17 Sep. 2018.

[28] Javanmard, Shaghayegh Haghjooy et al. “The effect of melatonin on endothelial dysfunction in patient undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting surgery.” Advanced biomedical research vol. 5 174. 28 Nov. 2016.

[29] Paul, Cristiana, and David M Brady. “Comparative Bioavailability and Utilization of Particular Forms of B12 Supplements With Potential to Mitigate B12-related Genetic Polymorphisms.” Integrative medicine (Encinitas, Calif.) vol. 16,1 (2017): 42-49.

[30] Wang, Peng et al. “The effects of pomegranate supplementation on biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction: A meta-analysis and systematic review.” Complementary therapies in medicine vol. 49 (2020): 102358.

[31] Flammer, Andreas J et al. “Dark chocolate improves coronary vasomotion and reduces platelet reactivity.” Circulation vol. 116,21 (2007): 2376-82.

[32] Barthelmes, Jens et al. “Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease and Flammer syndrome-similarities and differences.” The EPMA journal vol. 8,2 99-109. 6 Jun. 2017.

[33] Bender, Shawn B, and M Harold Laughlin. “Modulation of endothelial cell phenotype by physical activity: impact on obesity-related endothelial dysfunction.” American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology vol. 309,1 (2015): H1-8.