Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), more currently identified as metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) or metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), affects at least 25% of the world’s population and is the most common chronic liver disease. Its main characteristics include (Guo 2022):

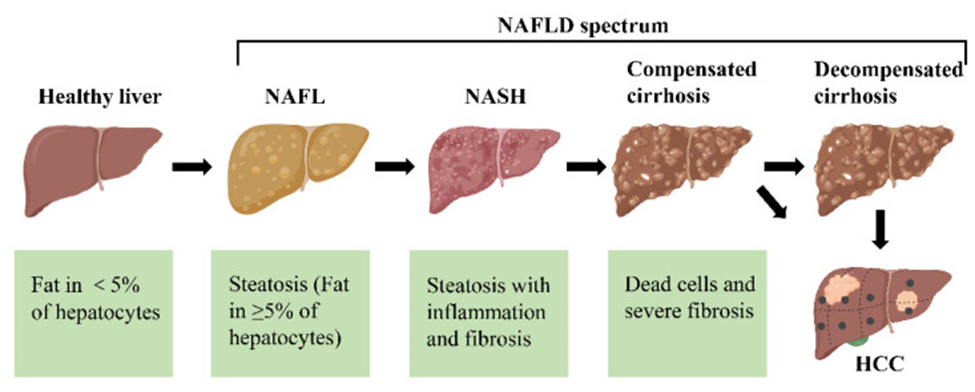

The different stages of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). First, the healthy livers develop non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) with hepatocellular steatosis as the main feature. If left untreated, NAFL may progress to a more severe form of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), defined as inflammation and fibrosis in addition to hepatocellular steatosis. As the disease progresses, NASH may progress to cirrhosis and even to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

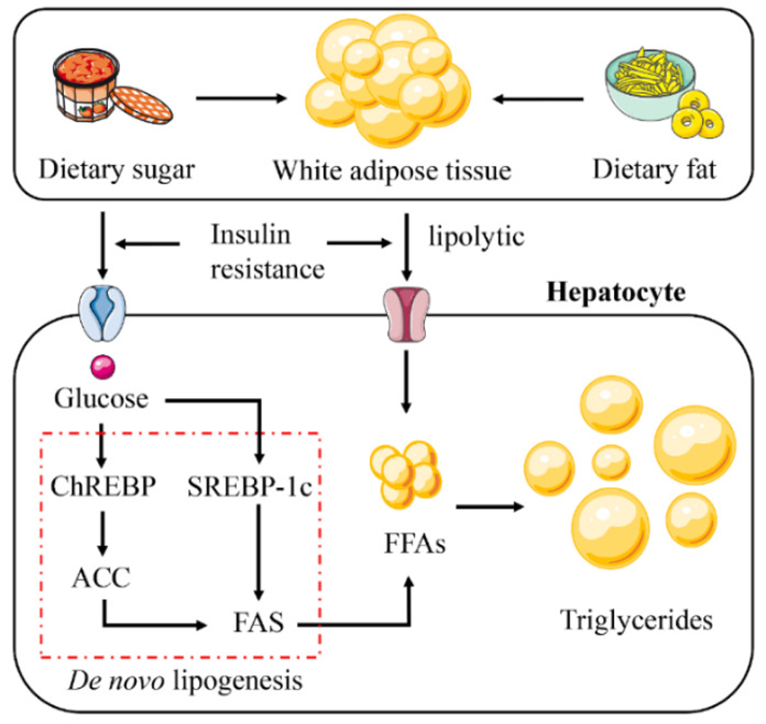

The increase in hepatic lipid accumulation is due to the absorption of large amounts of free fatty acids (FFAs) synthesized triglycerides by the liver from white adipose tissue (WAT), high-fat and high-sugar foods, and de novo lipogenesis (DNL). Insulin resistance plays a vital role in this process. Insulin resistance promotes glucose absorption and enhances the lipolysis of WAT. This leads to the activation of the DNL pathway. Abbreviations: ChREBP, carbohydrate response element binding protein; SREBP-1c, sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c; ACC, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; FAS, fatty acid synthase.

Source: Guo, Xiangyu et al. “Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Pathogenesis and Natural Products for Prevention and Treatment.” International journal of molecular sciences vol. 23,24 15489. 7 Dec. 2022, doi:10.3390/ijms232415489 This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

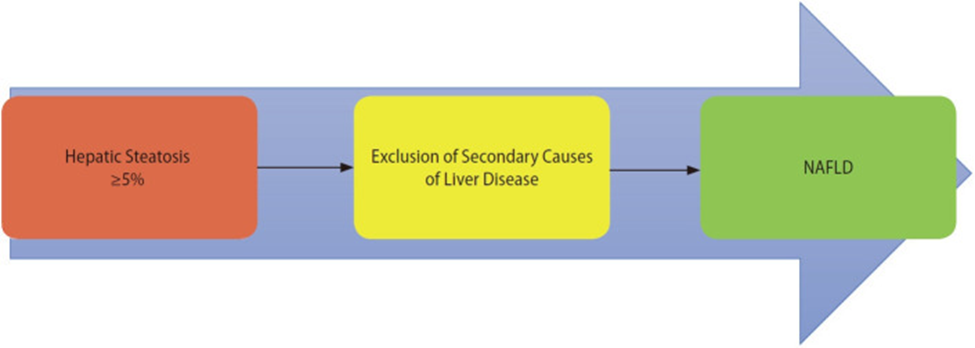

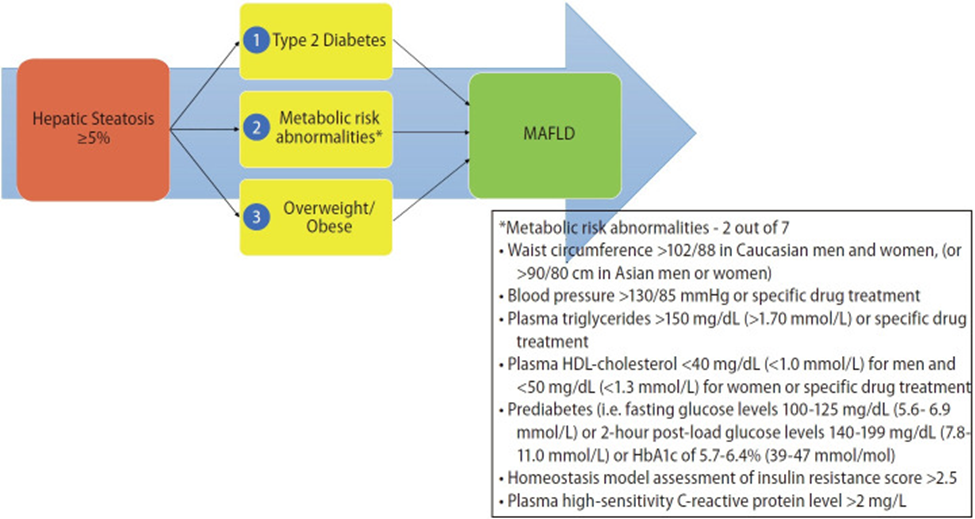

A panel of international experts from 22 countries propose a new definition that is both comprehensive yet simple for the diagnosis of MAFLD and is independent of other liver diseases. The criteria are based on evidence of hepatic steatosis, in addition to one of the following three criteria, namely overweight/obesity, presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, or evidence of metabolic dysregulation.

Increased cardiometabolic and MAFLD risk defined presence of at least two of the following metabolic at-risk criteria:

MAFLD may be present with other liver disorders:

* The AHA/NHLBI guidelines for metabolic syndrome recognize an increased risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes at waist-circumference thresholds of ≥94 cm in men and ≥80 cm in women and identify these as optional cut points for Caucasian individuals or populations with increased insulin resistance.

** These thresholds are derived from quantities beyond which a person is at more risk for alcohol related liver disease and may be in excess of the quantity needed to modify disease progression in MAFLD. This requires further study.

Source: Eslam, Mohammed et al. “A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement.” Journal of hepatology vol. 73,1 (2020): 202-209. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.039. This manuscript is made available under the CC BY NC user license https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Source: Gofton, Cameron et al. “MAFLD: How is it different from NAFLD?.” Clinical and molecular hepatology vol. 29,Suppl (2023): S17-S31. doi:10.3350/cmh.2022.0367 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/)

A meta-analysis of 22 observational studies comprising 379,801 subjects found that MAFLD was significantly associated with male gender, higher BMI, hypertension, diabetes, hypertriglyceridemia, lower HDL, elevated transaminases, and higher fibrosis scores than NAFLD. In general, there was a greater chance of being diagnosed with MAFLD versus NAFLD. However, researchers suggest that the current definition of MAFLD only accounted for 81.59% of those diagnosed with NAFLD in this analysis and that some patients may be missed using the proposed MAFLD criteria (Lim 2023).

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the European Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (EASL) have recently adopted the term “metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)” instead of MAFLD. However, diagnostic criteria are similar (AASLD, EASL).

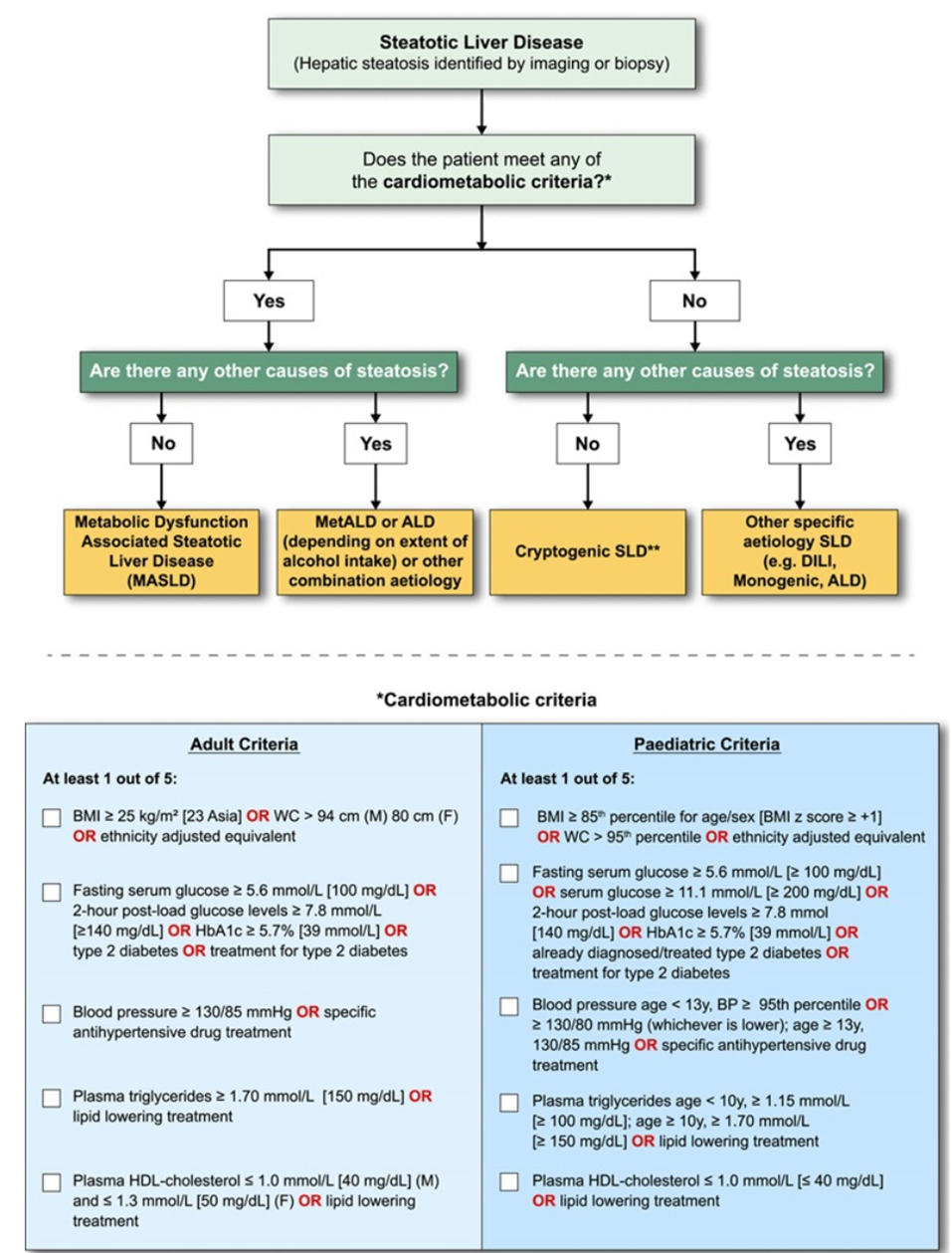

MASLD diagnostic criteria

In the presence of hepatic steatosis, the finding of any CMRF would confer a diagnosis of MASLD if there are no other causes of hepatic steatosis. If additional drivers of steatosis are identified, then this is consistent with a combination etiology. In the case of alcohol, this is termed MetALD or ALD, depending on extent of alcohol intake. In the absence of overt cardiometabolic criteria, other aetiologies must be excluded, and if none is identified, this is termed cryptogenic SLD although, depending on clinical judgment, it could also be deemed to be possible MASLD and, thus, would benefit from periodic reassessment on a case-by-case basis. In the setting of advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis, steatosis may be absent, requiring clinical judgment based on CMRFs and absence of other aetiologies. Abbreviations: ALD, alcohol-associated/related liver disease; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CMRF, cardiometabolic risk factors; DILI, drug-induced liver disease; MetALD, metabolic dysfunction and alcohol associated steatotic liver disease; SLD, steatotic liver disease; WC, waist circumference.

Source: Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature [published online ahead of print, 2023 Jun 24]. Hepatology. 2023;10.1097/HEP.0000000000000520. doi:10.1097/HEP.0000000000000520 Under a Creative Commons license

The terms MAFLD and MASLD have more in common than not and have achieved the objective of a more appropriate name for the condition (Chan 2023)

|

MAFLD |

MASLD |

|

|

Positive diagnostic criteria (i.e., defines what the disease is rather than what it is not) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Attributes the condition to its etiology |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Criteria |

Hepatic steatosis detected either by imaging techniques, blood biomarkers/scores, or liver history, plus |

Hepatic steatosis detected by imaging or biopsy, plus at least 1 of 5: |

|

Presence of other concomitant liver diseases |

Other concomitant liver diseases retain their own term |

Falls under a separate group (i.e., MetALD* or other combination etiology) |

*MetALD, i.e., weekly intake 140–350 g for females, 210–420 g for males (average daily 20–50 g for females, 30–60 g for males). MAFLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model for assessment of insulin resistance; hs-CRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; BMI, body mass index; MetALD, MASLD and increased alcohol intake.

Source: Chan, Wah-Kheong et al. “Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A State-of-the-Art Review.” Journal of obesity & metabolic syndrome vol. 32,3 (2023): 197-213. doi:10.7570/jomes23052. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0)

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty/steatotic liver disease can advance to a more severe, life-threatening form called metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) or even hepatocellular carcinoma and should be identified and addressed early. Appropriate holistic interventions include (Chan 2023):

AALSD. New MASLD Nomenclature. https://www.aasld.org/new-masld-nomenclature

Chan, Wah-Kheong et al. “Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A State-of-the-Art Review.” Journal of obesity & metabolic syndrome vol. 32,3 (2023): 197-213. doi:10.7570/jomes23052.

Eslam, Mohammed et al. “A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement.” Journal of hepatology vol. 73,1 (2020): 202-209. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.039

EASL. Multinational liver societies announce new “Fatty” liver disease nomenclature that is affirmative and non-stigmatising. https://easl.eu/news/new_fatty_liver_disease_nomenclature-2/

Gofton, Cameron et al. “MAFLD: How is it different from NAFLD?.” Clinical and molecular hepatology vol. 29,Suppl (2023): S17-S31. doi:10.3350/cmh.2022.0367. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/)

Guo, Xiangyu et al. “Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Pathogenesis and Natural Products for Prevention and Treatment.” International journal of molecular sciences vol. 23,24 15489. 7 Dec. 2022, doi:10.3390/ijms232415489

Lim, Grace En Hui et al. “An Observational Data Meta-analysis on the Differences in Prevalence and Risk Factors Between MAFLD vs NAFLD.” Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association vol. 21,3 (2023): 619-629.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2021.11.038