QUESTION:

Will parasites influence any other biomarkers markers besides eosinophils - such as liver enzymes or hemoglobin?

ANSWER:

Unfortunately, it is unlikely that you can rule out a parasitic infection or an allergy with blood chemistries alone. Parasitic infections must be tested specifically and treated appropriately, as they can have serious consequences.

Parasitic infection can be characterized by changes in blood chemistry, including red blood cells, white blood cells, and liver function tests.

Certain parasites enter circulation and can directly damage red blood cells and disrupt erythropoiesis. These include Babesia, Bartonella, and malaria parasites. Those causing malaria multiply in liver cells which rupture, releasing parasites that can then invade RBCs or promote RBC destruction. Parasitic infection can be fatal, and pathogens should be identified appropriately (McCullough 2014).

A stool culture can assist in identifying common parasites, including hookworm (Ascaris), tapeworm (Strongyloides), and Giardia protozoans. Gastrointestinal infections are often associated with diarrhea, excess flatulence, and abdominal discomfort. The risk of infection is increased with drinking well water or prolonged use of antibiotics. A tape test can be used to capture the larvae of pinworms, which lay their eggs at night in the perianal area (Pagana 2022).

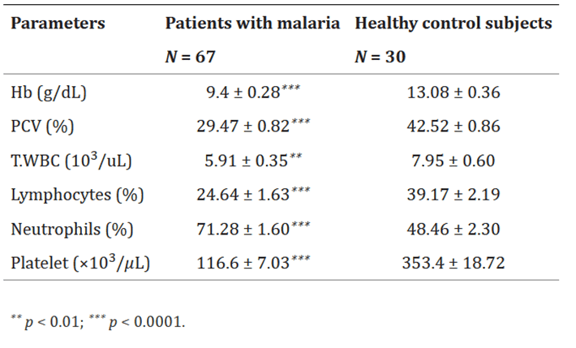

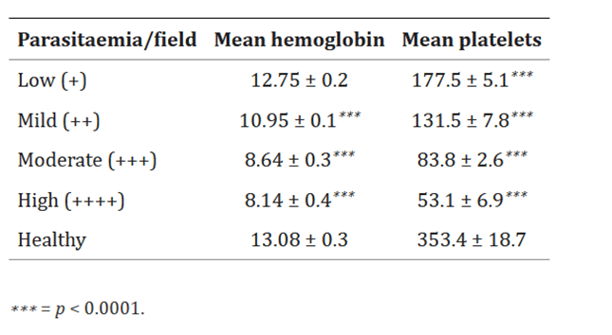

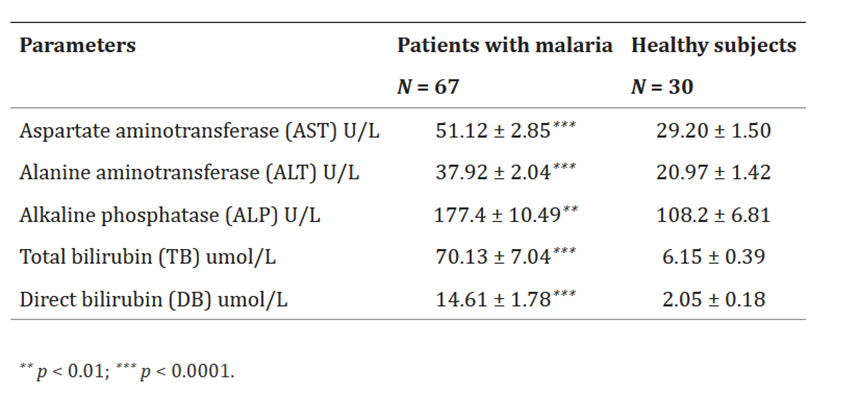

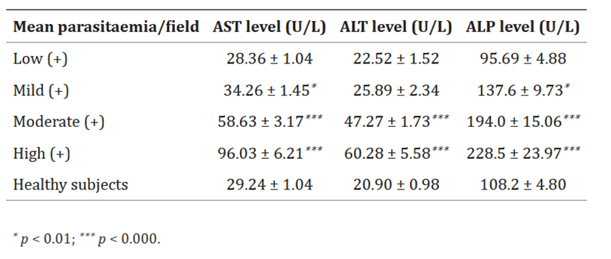

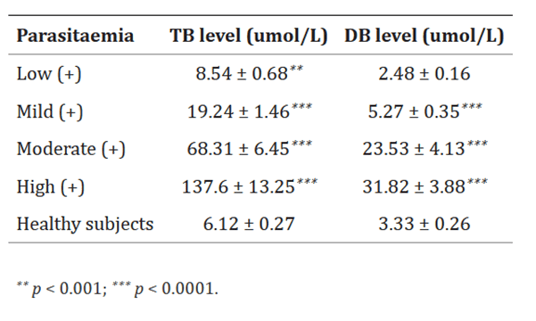

Malaria is associated with significantly decreased hemoglobin, packed cell volume, platelets, lymphocytes, and total white blood cells, and increased neutrophils. Levels of AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, and direct bilirubin increase significantly as the severity of infection increases, suggesting acute liver injury (Al-Salahy 2016). Advanced diagnostics should be used to identify malaria, including serial blood smear testing, rapid diagnostic tests, and molecular techniques (Pagana 2022).

Parasitic infection can cause an increase in IgE antibodies, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, and mast cells, though elevations are seen in allergic disorders as well and are not specific enough to be diagnostic (Pagana 2022, Vitte 2022). Serum iron may be decreased with parasitic infection as well but is nonspecific (Lazarte 2015).

Food allergies that are IgE-mediated can be fatal and should be identified and addressed (Kianifar 2016). Non-IgE mediated food sensitivities can be identified using strict elimination and rechallenge protocols, as well as leukocyte activation testing (Ali 2017, Chey 2022). Additional testing may be indicated for non–IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food-induced allergic disorders (non-IgE-GI-FAs), including food protein–induced enterocolitis syndrome, food protein–induced allergic proctocolitis, and food protein–induced enteropathy (Nowak-Węgrzyn 2015).

Comparison of hematological parameters between the cases of P. falciparum malaria infection and healthy subjects.

The level of hemoglobin and platelets in patient P. falciparum malaria with parasitaemia:

Changes in liver function biomarkers of the patient's P. falciparum malaria and healthy subjects:

Mean liver enzymes levels in parasitaemia P. falciparum malaria and healthy control subjects:

Mean total and direct bilirubin levels in parasitaemia P. falciparum malaria and healthy control subjects:

Source: Al-Salahy, Mohamed et al. “Parasitaemia and Its Relation to Hematological Parameters and Liver Function among Patients Malaria in Abs, Hajjah, Northwest Yemen.” Interdisciplinary perspectives on infectious diseases vol. 2016 (2016): 5954394. doi:10.1155/2016/5954394 This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License.

Commonly used standard tests used to diagnose parasitic diseases (CDC):

- A fecal (stool) exam, also called an ova and parasite test (O&P)

This test is used to find parasites that cause diarrhea, loose or watery stools, cramping, flatulence (gas) and other abdominal illness. CDC recommends that three or more stool samples, collected on separate days, be examined. This test looks for ova (eggs) or the parasite. - Endoscopy/Colonoscopy

Endoscopy is used to find parasites that cause diarrhea, loose or watery stools, cramping, flatulence (gas) and other abdominal illness. This test is used when stool exams do not reveal the cause of diarrhea. - Blood tests

Some, but not all, parasitic infections can be detected by testing your blood. Blood tests look for a specific parasite infection; there is no blood test that will look for all parasitic infections. There are two general kinds of blood tests that your doctor may order:

- Serology This test is used to look for antibodies or for parasite antigens produced when the body is infected with a parasite and the immune system is trying to fight off the invader.

- Blood smear This test is used to look for parasites that are found in the blood. By looking at a blood smear under a microscope, parasitic diseases such as filariasis, malaria, or babesiosis, can be diagnosed.

- X-ray, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan, Computerized Axial Tomography scan (CAT)

These tests are used to look for some parasitic diseases that may cause lesions in the organs.

References

Ali, Ather et al. “Efficacy of individualised diets in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised controlled trial.” BMJ open gastroenterology vol. 4,1 e000164. 20 Sep. 2017, doi:10.1136/bmjgast-2017-000164

Al-Salahy, Mohamed et al. “Parasitaemia and Its Relation to Hematological Parameters and Liver Function among Patients Malaria in Abs, Hajjah, Northwest Yemen.” Interdisciplinary perspectives on infectious diseases vol. 2016 (2016): 5954394. doi:10.1155/2016/5954394 This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License.

CDC, Diagnosis of Parasitic Diseases. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/references_resources/diagnosis.html

Chey, William D et al. “AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Role of Diet in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Expert Review.” Gastroenterology vol. 162,6 (2022): 1737-1745.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.12.248

Kianifar, Hamid Reza et al. “Sensitivity Comparison of the Skin Prick Test and Serum and Fecal Radio Allergosorbent Test (RAST) in Diagnosis of Food Allergy in Children.” Reports of biochemistry & molecular biology vol. 4,2 (2016): 98-103.

Lazarte, Claudia E., et al. "Nutritional status of children with intestinal parasites from a tropical area of Bolivia, emphasis on zinc and iron status." Food and Nutrition Sciences 6.04 (2015): 399.

McCullough, Jeffrey. “RBCs as targets of infection.” Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program vol. 2014,1 (2014): 404-9. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2014.1.404

Nowak-Węgrzyn, Anna et al. “Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergy.” The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology vol. 135,5 (2015): 1114-24. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.025

Vitte, Joana et al. “Allergy, Anaphylaxis, and Nonallergic Hypersensitivity: IgE, Mast Cells, and Beyond.” Medical principles and practice : international journal of the Kuwait University, Health Science Centre vol. 31,6 (2022): 501-515. doi:10.1159/000527481