We have all heard the old adage “you are what you eat.” Now we know that blood chemistry can reflect what we eat and how our bodies handle the type and amount we eat.

Blood chemistry analysis can reflect nutrient excesses and insufficiencies. You just need to know how the pieces fit together.

For example, excess intake of simple carbohydrates in someone with compromised blood glucose regulation can show up as increased fasting glucose, increased hemoglobin A1C, increased HOMA2-IR, and even increased triglycerides. More sophisticated biomarkers such as C-peptide, fructosamine, and 1,5 anhydroglucitol help round out the information needed to get to the root of the problem.

A chronically unhealthy diet will be reflected in a blood chemistry analysis, most likely as abnormal glucose regulation markers, dyslipidemia, abnormal oxidative stress markers, altered liver function enzymes. You will also see markers of nutrient imbalance, dehydration, and inflammation.

Let’s take a look at an unhealthy pattern like the Standard American Diet (SAD).

It is overloaded with highly processed foods high in trans- and saturated fats, refined carbs, processed meats, additives, toxins, pesticides, sugar-sweetened beverages, and excess alcohol.

Conversely, it is deficient in important vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, fiber, phytonutrients, and healthy fats and protein that support health and prevent disease.

Such a diet causes oxidative stress and contributes to chronic conditions including chronic inflammation, cancer, hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, endothelial dysfunction, heart disease, and even neurodegenerative diseases.1 2

Blood chemistry analysis associated with this unhealthy pattern can reveal blood chemistry results that are out of optimal range and possibly trending toward dysfunction:

Adherence to a healthy diet based on whole, plant-based foods and high-quality protein such as the Mediterranean diet, Dietary Approaches to Hypertension (DASH) diet, Nordic, or Anti-inflammatory diet will provide an abundance of fresh fruits and vegetables3 lean protein sources4 healthy fats5 complex carbohydrates6, fiber7, phytonutrients/phytochemicals8, vitamins9 and minerals10. This dietary pattern is not only good for humans but for their resident microbiota.11

Consistent adherence to a healthy diet will also be reflected in the blood chemistry analysis.

The HELENA cross-sectional study of 2330 adolescents revealed that the Mediterranean diet was positively associated with serum beta carotene, vitamin C, vitamin D, folate, holotranscobalamin, omega-3 fatty acids and fruit, and vegetable intake. A negative correlation was found between trans-fatty acids and energy-dense nutrient-deficient foods.12

In a prospective cohort study of 25,994 initially healthy women, adherence to a Mediterranean diet was associated with a 25% reduction in cardiovascular events and risk factors. Benefits were characterized by improvements in inflammatory markers, glucose metabolism, blood lipids, and blood pressure.13

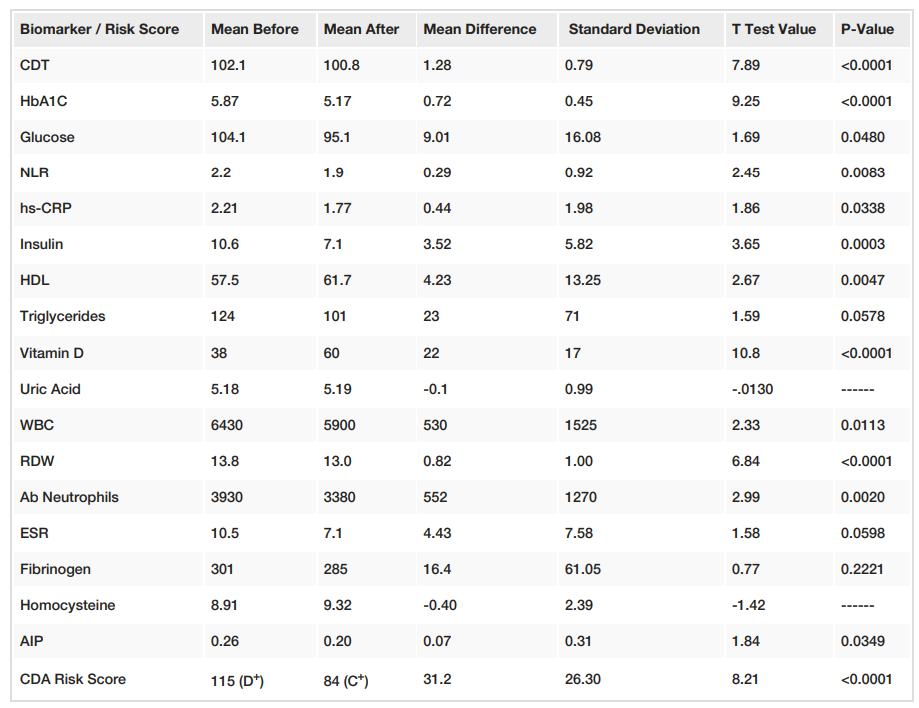

One comprehensive study of lifestyle and diet intervention demonstrated significant improvements in patients’ “Chronic Disease Assessment/CDA” grade, Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP), and chronic disease biomarker scores following a nine-month intervention period14. Many health issues were resolved in 5 to 6 months using the “Health Revival Process.” Researchers estimated a total savings of $217,026 by reducing pharmaceutical use in the 70-person cohort.

Targeted nutrition intervention and supplementation resulted in significant biomarker improvements in the study group as a whole, as well as in specific cases:

Group biomarker changes in 70-person cohort over 9-month intervention period:

Source: Lewis, Thomas J et al. “Reduction in Chronic Disease Risk and Burden in a 70-Individual Cohort Through Modification of Health Behaviors.” Cureus vol. 12,8 e10039. 26 Aug. 2020, doi:10.7759/cureus.10039 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Health Revival researchers remind us that pharmaceutical-based interventions without corresponding lifestyle changes fall short in the effort to prevent chronic disease.15

“Pharmaceuticals prescribed based on test results have poor absolute statistical success at preventing or reversing disease… cardiovascular disease mortality, managed with statin drugs, blood pressure medications, and other usual care approaches across broad members of the U.S. population, increased nationally by 4.3% between 2011 and 2016.”

A chronically unhealthy diet will also contribute to compromised nutritional status and organ function, macronutrient and micronutrient imbalance, and hydration issues which can also be assessed using functional blood chemistry analysis.

You won’t know what’s going on inside your patient’s body until you take a look at their blood.

1. Sharifi-Rad, Mehdi et al. “Lifestyle, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Back and Forth in the Pathophysiology of Chronic Diseases.” Frontiers in physiology vol. 11 694. 2 Jul. 2020, doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.00694

2. Kopp, Wolfgang. “How Western Diet And Lifestyle Drive The Pandemic Of Obesity And Civilization Diseases.” Diabetes, metabolic syndrome and obesity : targets and therapy vol. 12 2221-2236. 24 Oct. 2019, doi:10.2147/DMSO.S216791

3. Ko, Byung-Joon et al. “Diet quality and diet patterns in relation to circulating cardiometabolic biomarkers.” Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) vol. 35,2 (2016): 484-490. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2015.03.022

4. Pistollato, Francesca, and Maurizio Battino. "Role of plant-based diets in the prevention and regression of metabolic syndrome and neurodegenerative diseases." Trends in food science & technology (2014).

5. Chiu, Sally et al. “Comparison of the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet and a higher-fat DASH diet on blood pressure and lipids and lipoproteins: a randomized controlled trial.” The American journal of clinical nutrition vol. 103,2 (2016): 341-7. doi:10.3945/ajcn.115.123281

6. Iddir, Mohammed et al. “Strengthening the Immune System and Reducing Inflammation and Oxidative Stress through Diet and Nutrition: Considerations during the COVID-19 Crisis.” Nutrients vol. 12,6 1562. 27 May. 2020, doi:10.3390/nu12061562

7. Mayne, Susan T. “Antioxidant nutrients and chronic disease: use of biomarkers of exposure and oxidative stress status in epidemiologic research.” The Journal of nutrition vol. 133 Suppl 3 (2003): 933S-940S. doi:10.1093/jn/133.3.933S

8. Castro-Barquero, Sara et al. “Dietary Strategies for Metabolic Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review.” Nutrients vol. 12,10 2983. 29 Sep. 2020, doi:10.3390/nu12102983

9. Yu, Edward et al. “Diet, Lifestyle, Biomarkers, Genetic Factors, and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in the Nurses' Health Studies.” American journal of public health vol. 106,9 (2016): 1616-23. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303316

10. Dragsted, Lars O et al. “Dietary and health biomarkers-time for an update.” Genes & nutrition vol. 12 24. 29 Sep. 2017, doi:10.1186/s12263-017-0578-y

11. Landberg, Rikard, and Kati Hanhineva. “Biomarkers of a Healthy Nordic Diet-From Dietary Exposure Biomarkers to Microbiota Signatures in the Metabolome.” Nutrients vol. 12,1 27. 20 Dec. 2019, doi:10.3390/nu12010027

12. Aparicio-Ugarriza, Raquel et al. “Relative validation of the adapted Mediterranean Diet Score for Adolescents by comparison with nutritional biomarkers and nutrient and food intakes: the Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence (HELENA) study.” Public health nutrition vol. 22,13 (2019): 2381-2397. doi:10.1017/S1368980019001022

13. Ahmad, Shafqat et al. “Assessment of Risk Factors and Biomarkers Associated With Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Among Women Consuming a Mediterranean Diet.” JAMA network open vol. 1,8 e185708. 7 Dec. 2018, doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5708

14. Lewis, Thomas J et al. “Reduction in Chronic Disease Risk and Burden in a 70-Individual Cohort Through Modification of Health Behaviors.” Cureus vol. 12,8 e10039. 26 Aug. 2020, doi:10.7759/cureus.10039 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

15. ibid.